It turns out that one of the Grand Old Party’s biggest—and least discussed—challenges going into 2016 is lying in plain sight, written right into the party’s own nickname. The Republican Party voter is old—and getting older, and as the adage goes, there are two certainties in life: Death and taxes. Right now, both are enemies of the GOP and they might want to worry more about the former than the latter.

There’s been much written about how millennials are becoming a reliable voting bloc for Democrats, but there’s been much less attention paid to one of the biggest get-out-the-vote challenges for the Republican Party heading into the next presidential election: Hundreds of thousands of their traditional core supporters won’t be able to turn out to vote at all.

The party’s core is dying off by the day.

Since the average Republican is significantly older than the average Democrat, far more Republicans than Democrats have died since the 2012 elections. To make matters worse, the GOP is attracting fewer first-time voters. Unless the party is able to make inroads with new voters, or discover a fountain of youth, the GOP’s slow demographic slide will continue election to election. Actuarial tables make that part clear, but just how much of a problem for the GOP is this?

Since it appears that no political data geek keeps track of voters who die between elections, I took it upon myself to do some basic math. And that quick back-of-the-napkin math shows that the trend could have a real effect in certain states, and make a battleground states like Florida and Ohio even harder for the Republican Party to capture.

By combining presidential election exit polls with mortality rates per age group from the U.S. Census Bureau, I calculated that, of the 61 million who voted for Mitt Romney in 2012, about 2.75 million will be dead by the 2016 election. President Barack Obama’s voters, of course, will have died too—about 2.3 million of the 66 million who voted for the president won’t make it to 2016 either. That leaves a big gap in between, a difference of roughly 453,000 in favor of the Democrats.

Here is the methodology, using one age group as an example: According to exit polls, 5,488,091 voters aged 60 to 64 years old supported Romney in 2012. The mortality rate for that age group is 1,047.3 deaths per 100,000, which means that 57,475 of those voters died by the end of 2013. Multiply that number by four, and you get 229,900 Romney voters aged 60-to-64 who will be deceased by Election Day 2016. Doing the same calculation across the range of demographic slices pulled from exit polls and census numbers allows one to calculate the total voter deaths. It’s a rough calculation, to be sure, and there are perhaps ways to move the numbers a few thousand this way or that, but by and large, this methodology at least establishes the rough scale of the problem for the Republicans—a problem measured in the mid-hundreds of thousands of lost voters by November 2016. To the best of my knowledge, no one has calculated or published better voter death data before.

“I’ve never seen anyone doing any studies on how many dead people can’t vote,” laughs William Frey, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who specializes in demographic studies. “I’ve seen studies on how many dead people do vote. The old Daley Administration in Chicago was very good at that.”

Frey points out that, since Republicans are getting whiter and older, replacing the voters that leave this earth with young ones is essential for them to be competitive in presidential elections. But the key question is whether these election death rates will make any real difference. There are so many other variables that dead voters aren’t necessarily going to be a decisive factor.

“The [GOP] does rely too much on older and white voters, and especially in rural areas, deaths from this group can be significant,” Frey says. “But millennials (born 1981 to 1997) now are larger in numbers than baby boomers ([born] 1946 to 1964), and how they vote will make the big difference. And the data says that if Republicans focus on economic issues and stay away from social ones like gay marriage, they can make serious inroads with millennials.”

But what if Republicans aren’t able to win over a larger share of the youth vote? In 2012, there were about 13 million in the 15-to-17 year-old demo who will be eligible to vote in 2016. The previous few presidential election cycles indicate that about 45 percent of these youngsters will actually vote, meaning that there will about 6 million new voters total. Exit polling indicates that age bracket has split about 65-35 in favor of the Dems in the past two elections. If that split holds true in 2016, Democrats will have picked up a two million vote advantage among first-time voters. These numbers combined with the voter death data puts Republicans at an almost 2.5 million voter disadvantage going into 2016.

Even though the Republicans are losing at both ends of the political voter lifeline, there are multiple caveats worth keeping in mind. The first is that the popular vote is largely meaningless in the Electoral College system and states have voter demographics that don’t necessarily reflect the national numbers. Second, a larger percentage of young people stay at home in non-competitive states like California. Older citizens still tend to vote in big numbers in those states, so a large percentage of those that die between elections are in states that don’t really matter much on Election Day. The flipside is the youth vote is concentrated in the states that matter.

“The states have different voter populations based on age, and so the influence of having more of your voter base dying is not easy to extrapolate into meaningful numbers,” says Susan MacManus, a political science professor at the University of South Florida. “That doesn’t mean having more of your voter base dying is a good thing, but it is hard to quantify.”

“And some of the studies indicate that the older people in Florida live longer because of their more active lifestyle,” she adds.

I decided to run some swing state numbers to see if the dead voter numbers might tip the balance one way or another. In Virginia and Ohio, it appears that the numbers of voters who died between 2012 and 2016 won’t be much of a factor. More Romney than Obama voters will have died in those states between 2012 and 2016 (about 7,000 in Virginia and about 30,000 in Ohio), but those totals are a very small speck in the big picture; the Ohio figure, for instance, represents only about a sixth of Obama’s 167,000-vote margin of victory. Not good numbers for Republicans, but not particularly significant either.

But in MacManus’s Florida, with its aging population—it’s ranked 47th among states in median age—there are not surprisingly a large numbers of voters who will have died between 2012 and 2016: About 244,000 Romney voters and 187,000 Obama voters. That’s a difference of 57,000—a total larger than the population of nearly 26 of the state’s 67 counties. What makes that number particularly significant, of course, is the narrowness of presidential victories in Florida: Obama won the state by only about 73,000 votes in 2012 and, as everyone remembers, George W. Bush only won the state by only 537 votes in 2000. In tight swing states in a nation that often seems close to 50-50, a few thousand votes here and there can matter.

Keep in mind there are major caveats with the Florida numbers.

For starters, seniors are relocating to Florida all the time, so it’s not clear how much younger Florida will skew in 2016. Brookings Institution’s Frey says that, once again, Florida will be very complex this time around. “The Hispanic vote is not a monolithic group like in other states, because of the influence of the Cubans and the Puerto Ricans and South Americans and the now growing Mexican population,” he explains. “The Republicans seem to be doing a better job of attracting young people in Florida, based on the midterm results. There is also some indication that Hillary Clinton might do well with older women. She might take a decent number of older women in Florida who voted for Romney.”

Regardless, political demographers are seeing this election as a watershed. Millennials now have higher numbers than Baby Boomers, and the mortality rates will expand that difference in coming elections. The very conservative Silent Generation, born between 1925 and 1942, is declining at a rapid pace. The mortality rate for 70-to-74 year-olds is 6,058.4 per 100,000 each year, compared to 110.1 for the 30-to-34 age group. With each death, a little political power passes from one generation to the next.

If all this seems confusing, it is to a certain extent, because there are so many uncertainties about this 2016 election. But there is one certainty: Dead people don’t vote, at least not as much as they did in Chicago in 1960. When the political operatives start dissecting and predicting how the electorate is going to show in 2016, they should take into account not only the who and why of the ones that will vote, but also the ones who aren’t showing up this time around because they’ve kicked the bucket.

No carefully-crafted campaign message can change that

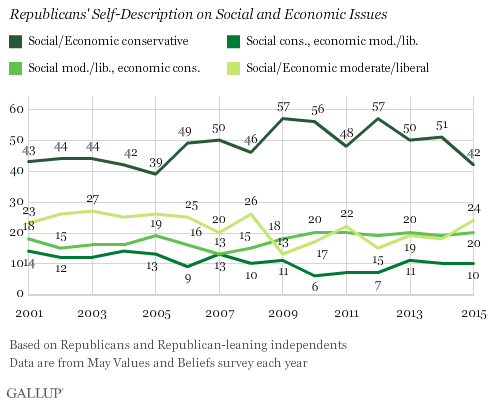

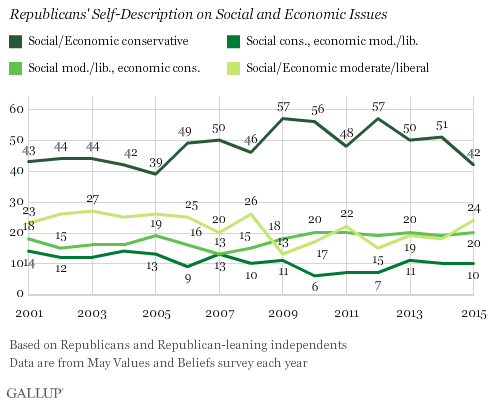

The percentage of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents who describe themselves as both social and economic conservatives has dropped to 42%, the lowest level Gallup has measured since 2005. The second-largest group of Republicans (24%) see themselves as moderate or liberal on both social and economic issues, while 20% of all Republicans are moderate or liberal on social issues but conservative on economic ones.

These data are from Gallup's Values and Beliefs poll, which since 2001 has included questions asking Americans to rate themselves as conservative, moderate or liberal on social and economic issues. These trends show not only that Americans as a whole have become less likely to identify as social or economic conservatives, but also that Republicans' views are changing along the same lines.

This change in recent years has been significant. The percentage of Republicans identifying as conservative on both dimensions has dropped 15 percentage points since 2012, largely offset by an increase in the percentage who identify as moderate or liberal on both dimensions. Still, the current ideological positioning of Republicans is not unprecedented; the proportion of social and economic conservatives was as low or lower from 2001 through 2005.

Republicans' Ideology Varies Significantly by Age

The percentage of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents who are conservative on both social and economic issues rises steadily with age. An analysis of aggregated surveys conducted since the 2012 election shows that the size of the social and economic conservative group is twice as large among Republicans aged 65 and older as it is among those aged 18 to 29. This may be good news for GOP candidates who are running on a conservative platform and can assume that older Republicans will constitute a sizable portion of primary and caucus voters. But it would not be such good news when it comes to the challenge of energizing a broader base of Republican voters to come out to vote in the typically higher-turnout general election.

Implications

The recent shift in how Republicans view themselves ideologically may have significant implications for the coming GOP presidential nomination fight, particularly in terms of how the candidates will try to position themselves to maximize their appeal. Republican candidates are dealing with a party base that is today significantly more ideologically differentiated than it has been over the past decade. A GOP candidate positioning himself or herself as conservative on both social and economic issues theoretically will appeal to less than half of the broad base of rank-and-file party members. This opens the way for GOP candidates who may want to position themselves as more moderate on some issues, given that more than half of the party identifiers are moderate or liberal on social or economic dimensions.

The caveat in these campaign decisions is that not all Republicans are involved in the crucial early primary and caucus voting that helps winnow the pack of presidential candidates down to a winner. Ideology on both social and economic issues is strongly related to age, and primary voters tend to skew older than the overall party membership. This could benefit a more conservative candidate in the primary process, but that advantage could dissipate in the general election.

Democratic candidates will be dealing with party identifiers who are mostly moderate or liberal on social and economic issues, with a significant divide between these two groups. A forthcoming story will look at the Democratic ideological situation in detail.

Survey Methods

Results for the most recent Gallup poll are based on telephone interviews conducted May 6-10, 2015, with a random sample of 1,024 adults, aged 18 and older, living in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. For results based on the total sample of national adults, the margin of sampling error is ±4 percentage points at the 95% confidence level.

Results for the aggregated Gallup polls conducted in 2013-2015 are based on telephone interviews with a random sample of 3,587 adults, aged 18 and older. For results based on this sample, the margin of sampling error is ±2 percentage points at the 95% confidence level. All reported margins of sampling error include computed design effects for weighting.

Each sample of national adults includes a minimum quota of 50% cellphone respondents and 50% landline respondents, with additional minimum quotas by time zone within region. Landline and cellular telephone numbers are selected using random-digit-dial methods.